How AI is Rewriting Geopolitics

The global struggle to secure infrastructure, energy, and compute capacity is emerging as the core driver of geopolitical influence in AI.

Introduction – The Geopolitics of AI

Artificial intelligence (AI) is no longer just a story of algorithms and innovation; it’s a contest over infrastructure, energy, and statecraft. As JPMorgan’s October 2025 report Decoding the New Global Operating System argues, AI is fast becoming “the most consequential technological development of the 21st century,” one capable of redefining “the rules of global trade, alliances, and even war” (p. 2). Since the release of ChatGPT nearly three years ago, AI has exploded into a driver of economic growth and geopolitical tension. In the United States alone, JPMorgan notes, AI-related stocks accounted for nearly 80 percent of earnings growth and 90 percent of capital spending growth since November 2022 (p. 2). But the report stresses that the global story isn’t just about market capitalizations or clever chatbots. It’s about power grids, semiconductor supply chains, and national strategies.

The world’s superpowers are now competing to control the physical backbone of intelligence: chips, data centers, and the electricity that fuels them. Seven “strategic axes” define this new global order, from China’s state-led self-reliance and America’s private-sector push to Europe’s quest for tech sovereignty and the Middle East’s investment surge in AI infrastructure. The friction between these axes is redrawing the global map of power.

Axis 1 – An Assertive China

China, the report argues, has fused state planning and private innovation into a formidable AI engine. “China has emerged as a pivotal force of influence in the AI ecosystem globally,” with ambitions to lead the world through what Xi Jinping calls a “whole-of-nation” approach to AI self-sufficiency (p. 5).

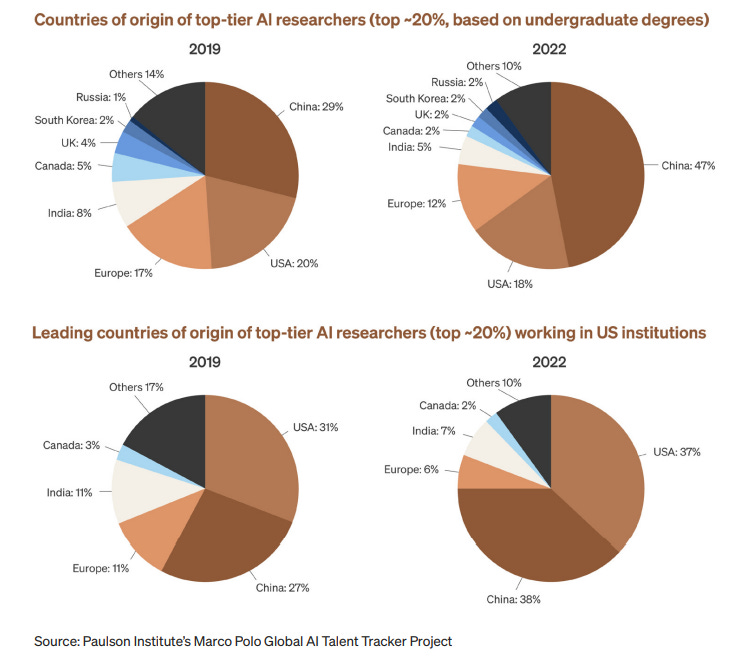

Since 2014, China has operated a $100 billion semiconductor fund, followed by another $8.5 billion for AI start-ups in 2025 (p. 6). Its universities now host over 2,000 undergraduate AI programs, and China awards nearly twice as many science and engineering PhDs as the U.S. (p. 6) . Meanwhile, local governments have built entire “AI neighborhoods,” such as Hangzhou’s Dream Town, to incubate start-ups and experiment with smart infrastructure (p. 6).

China’s “Eastern Data, Western Compute” initiative orders massive data centers in the country’s less populated western provinces, pairing cheap energy with high-performance compute (p. 6). This geographic strategy of moving compute closer to abundant energy is emblematic of Beijing’s model: coordinated, long-term, and physical.

Beijing’s push is not just about technology but diffusion. The government’s “AI+” Opinions set targets for over 90 percent adoption of intelligent agents and smart terminals by 2030 (p. 8). Cities such as Beijing and Shenzhen now issue compute vouchers to subsidize AI use for local firms and is part of what JPMorgan calls a “policy-driven diffusion sprint.”

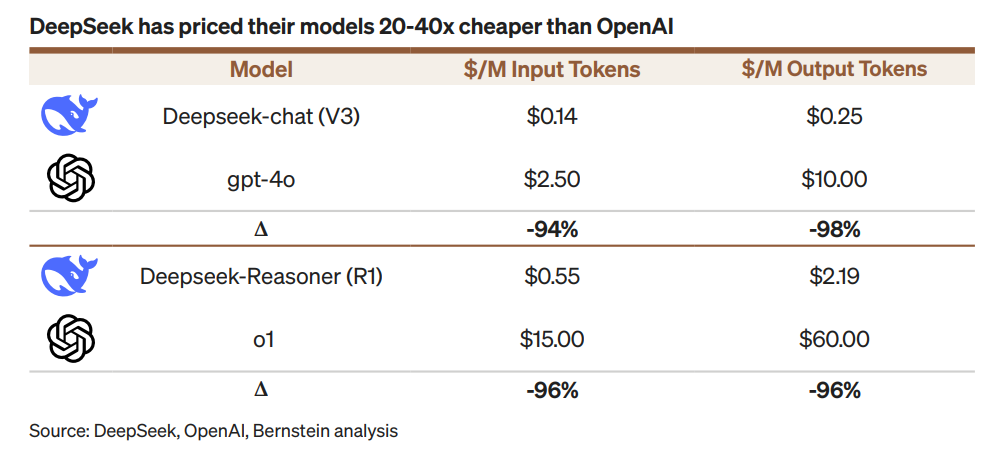

Then there’s DeepSeek, China’s homegrown generative model. Priced 20–40 times cheaper than OpenAI’s ChatGPT (p. 9) , DeepSeek’s open-source approach offers developing countries low-cost access to automation tools. A U.S. National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST) report, however, found American models about 35 percent more efficient overall when quality and security were included (p. 8). Still, the pricing gap gives China a strategic foothold in emerging markets.

China’s energy advantage is equally decisive. With a national grid reserve margin of 80–100 percent, China can plan capacity years ahead of demand, unlike the U.S. grid’s fragmented ~15 percent margin (p. 10). This foresight turns energy from a utility into a geopolitical lever.

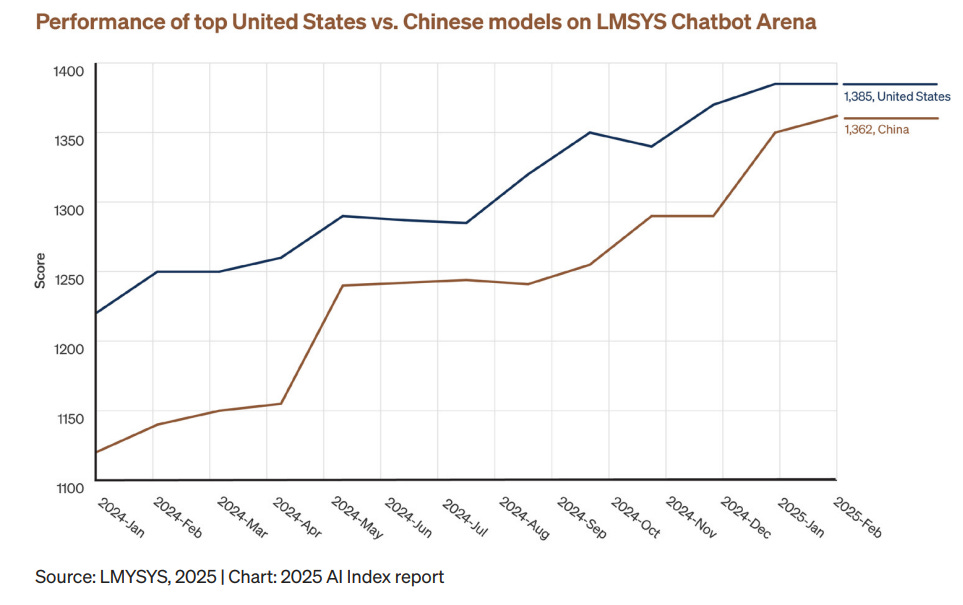

Finally, China has shifted its diplomatic tone. At the 2025 World AI Conference, Premier Li Qiang called for “global coordination” and shared AI governance (p. 11), a message seen as both cooperative and competitive. JPMorgan concludes that despite U.S. export controls, China’s combination of state support, private innovation, and energy planning “is likely to mean it remains a close competitor—and potentially dominant power—to the United States in AI” (p. 11).

Axis 2 – A Repositioned United States

Across the Pacific, America’s AI strategy rests on a paradox: a market-driven system increasingly guided by national-security imperatives. JPMorgan calls the U.S. “the global leader in AI,” but notes that 2025 marked a dramatic repositioning under the AI Action Plan and executive orders (p. 12).

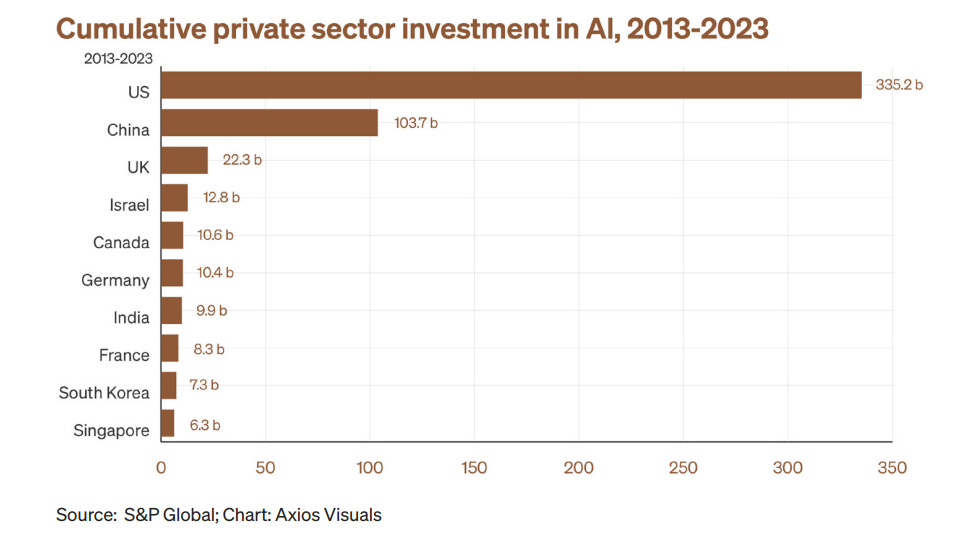

The investment scale is enormous. In 2024, American firms poured $109.1 billion into AI, twelve times China’s $9.3 billion (p. 12). By mid-2025, another $104 billion had already been raised. Projects like Stargate, a $500 billion private-sector venture involving OpenAI, SoftBank, and Oracle symbolize the fusion of government and capital (p. 15).

The AI Action Plan is built on three pillars: innovation, infrastructure, and international AI diplomacy (p. 15). It fast-tracks permits for data-center construction, mobilizes federal lands for energy projects, and allocates $100 billion to critical-mineral mining (p. 15). The U.S. government has even taken an equity stake in Intel, treating semiconductors as strategic assets rather than purely commercial goods (p. 27).

Yet JPMorgan warns that U.S. leadership carries fragility. Energy bottlenecks and regulatory gridlock could constrain growth (p. 13). The nation’s patchwork of private utilities struggles to match China’s centralized capacity planning, while tariffs on metals and minerals raise costs for AI infrastructure.

Export controls have become a flash point. Congress is debating the Chip Security Act and No Advanced Chips for the CCP Act to tighten restrictions on AI hardware sales to China (p. 13) . Some lawmakers argue that flooding global markets with U.S. chips would lock in “ecosystem dependence,” while others fear reverse-engineering by Beijing.

Ultimately, JPMorgan warns that while the U.S. “maintains top billing in many dimensions of AI leadership,” domestic polarization and trade tensions “may be in tension with the nation’s stated AI goals globally” (p. 14). In other words, America’s greatest rival may be its own politics.

Axis 3 – Europe’s Pursuit for Tech Sovereignty

Europe’s relationship with AI is defined less by a race for dominance and more by a struggle for independence. The EU’s push for “tech sovereignty,” JPMorgan writes, aims to reduce reliance on U.S. tech giants and enhance security and competitiveness (p. 16).

Through the AI Continent Action Plan and Competitiveness Compass (2025), Europe is pouring resources into computing power and infrastructure. The vision of a “EuroStack” (a homegrown digital ecosystem covering AI and semiconductors) could cost €300 billion by 2035 (p. 16). France alone has pledged €109 billion for AI infrastructure, and Brussels is experimenting with public-procurement preferences for European firms.

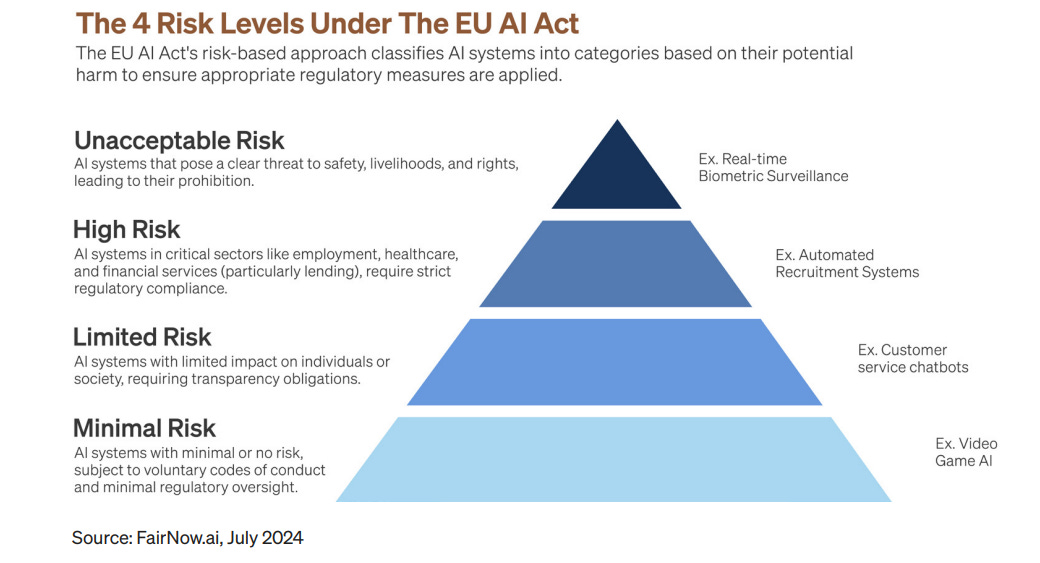

Europe’s regulatory flagship is the AI Act, which divides AI systems into four risk tiers, from “unacceptable” to “minimal.” The most serious violations can trigger fines of up to 7 percent of global annual turnover or €35 million (p. 17). But Washington views the EU’s rule-making as protectionist. After a February 2025 clash at the Global AI Summit in Paris, the U.S. imposed retaliatory tariffs on European products (p. 16).

Meanwhile, post-Brexit Britain is charting its own course. A Technology Prosperity Deal with the U.S. brought £31 billion in AI investments from companies like Microsoft and NVIDIA (p. 17). JPMorgan notes that Europe’s ambition to write the rules for AI could either anchor a values-based order or splinter Western unity: “The direction of EU–U.S. relations may have major consequences for whether free-market nations can maintain an allied posture in shaping the geopolitical landscape of AI” (p. 17).

Axis 4 – Middle East investment is powering global AI infrastructure

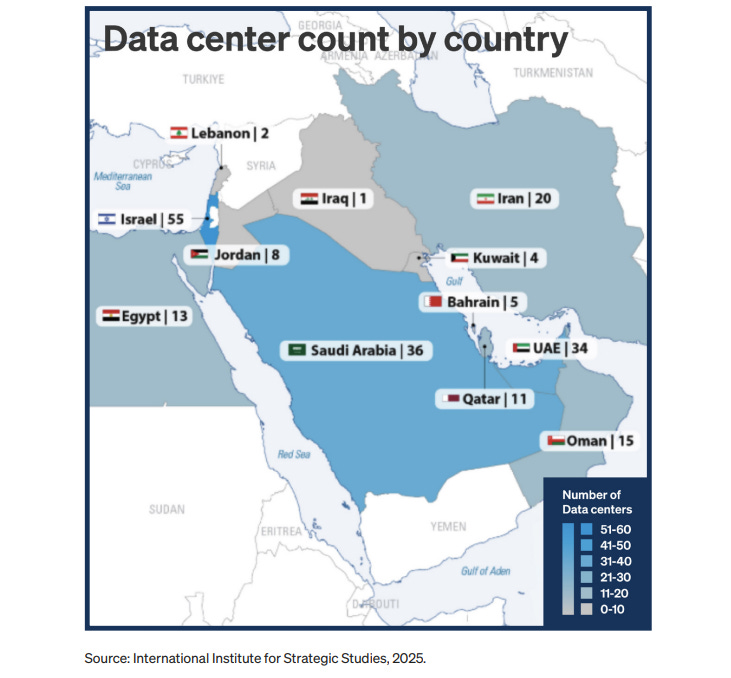

JPMorgan’s fourth axis spotlights how Middle Eastern nations are converting oil wealth into AI infrastructure. The region, the report notes, is “heavily investing in AI infrastructure, driven by a desire to diversify economies beyond oil and become global leaders in the AI race” (p. 20).

Sovereign wealth funds anchor the strategy. Saudi Arabia’s Public Investment Fund backs Humain, “a $77 billion venture focused on building AI infrastructure” (p. 21). The UAE’s MGX, founded by Mubadala, is “targeting over $100 billion in assets for AI infrastructure, chips, and core technologies,” while the UAE National AI Strategy 2031 aims for “AI to contribute 40 percent of GDP by 2031” (p. 21). Qatar’s Investment Authority is likewise investing in data centers and semiconductor ventures (p. 21).

Partnerships with global tech firms deepen this push. The report lists Amazon’s $5 billion AI Zone in Saudi Arabia, a Google Cloud–PIF deal worth up to $10 billion, Equinix’s $1 billion 100 MW data center, Oracle’s $14 billion cloud investment, and Huawei’s $400 million pledge to Riyadh’s cloud sector (p. 22). These collaborations pair foreign expertise with local energy and capital.

JPMorgan underscores the contrast in scale: “The United States is by far the world’s leader in data center facilities, with 5,000 facilities compared to just a few hundred in the Middle East.” (p. 21). Still, it argues, this investment drive gives Gulf economies new leverage, transforming the region from a supplier of fuel to a supplier of compute power.

Axis 5 – Talent, Populism, and the Workforce

AI’s rapid rise isn’t just redrawing economic maps, it’s stirring political ones. As JPMorgan notes, “the rise of populist political movements has been a feature of geopolitics over the past decade,” and their intersection with AI is reshaping labor markets and public sentiment (p. 24).

The first flashpoint is jobs. Analysts predict AI could displace 12 million workers by 2030, and unions are already mobilizing to protect their members (p. 24). In the U.S., dockworkers went on strike to limit automation, while Hollywood’s writers and actors negotiated guardrails against AI-generated scripts and likenesses. Across Europe, IG Metall, the continent’s largest industrial union, has pushed for “co-determination” rights on how AI tools enter workplaces, demanding transparency, worker participation, and algorithmic oversight (p. 24).

Populism’s other front is distrust of Big Tech. JPMorgan highlights how leaders across the U.S. and Europe now view major American tech firms with suspicion, citing monopoly power and weak accountability (p. 24). Regulators on both sides of the Atlantic are pressing antitrust cases, imposing record fines, and tightening AI and digital-market rules.

Finally, the political backlash is likely to reshape policy itself. The report warns that anxiety over job losses and immigration may drive “greater tech sovereignty,” especially in Europe, fragmenting the global regulatory landscape (p. 25). In the U.S., demand for AI talent could soften anti-immigration pressure, even as skepticism toward tech giants fuels a new bloc of “Little Tech” advocates (startups and investors positioning themselves as the nimble alternative).

Axis 6 – Energy, Hardware, and Componentry

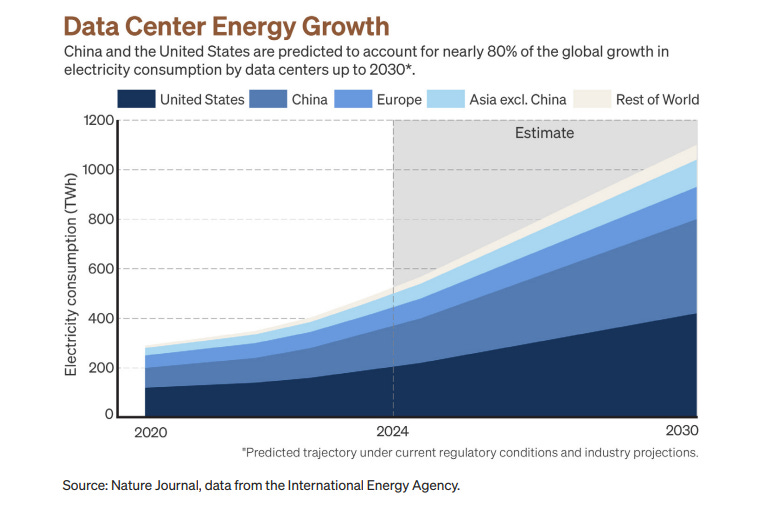

AI’s geopolitical contest now depends on who controls energy, hardware, and raw materials. JPMorgan notes that “it’s difficult to overstate the profound role that energy and infrastructure-level resources are playing in motivating the geopolitical positioning of AI-focused governments” (p. 26). Nations are racing to secure these foundations: China is expanding renewable sources like solar and wind to power its AI infrastructure, while the United States pursues “all-out American energy dominance,” planning to build as much new capacity as China by 2026 through fossil and nuclear projects (p. 26).

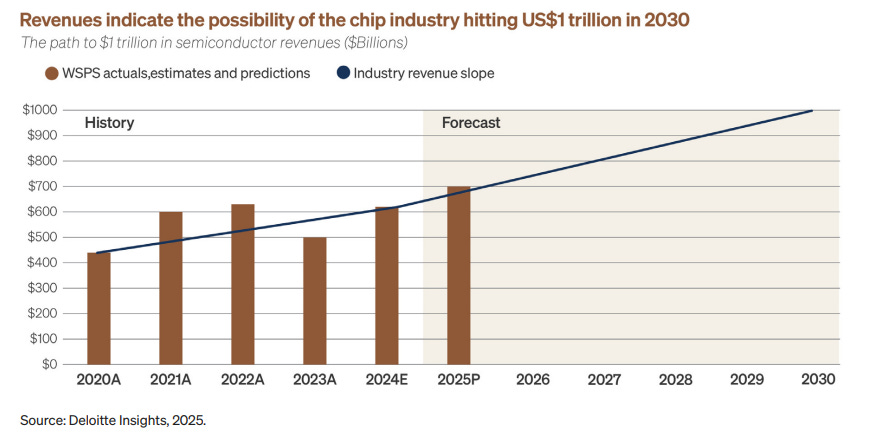

Semiconductors remain the key geopolitical chokepoint. The United States is boosting domestic manufacturing through the CHIPS Act, while South Korea invests to maintain its leadership (p. 27). The U.S. also tightened export controls, allowing NVIDIA and AMD to sell H20 and MI308 chips to China only if 15% of revenues go to the U.S, while continuing to block the sale of the most advanced GPUs. The government’s 10% equity stake in Intel reflects how semiconductors are now treated as strategic assets rather than commercial goods (p. 27).

JPMorgan adds that industrial materials like steel, aluminum, copper, and critical minerals have gained geopolitical weight, influencing both trade policy and defense negotiations, including recent U.S.–Ukraine discussions on mineral access (p. 27). The report concludes that “the race for AI leadership is reshaping a broad spectrum of priorities”, from energy security to supply chains and raw material access, illustrating that control over infrastructure now defines technological power (p. 28).

Axis 7 – The Future of Defense

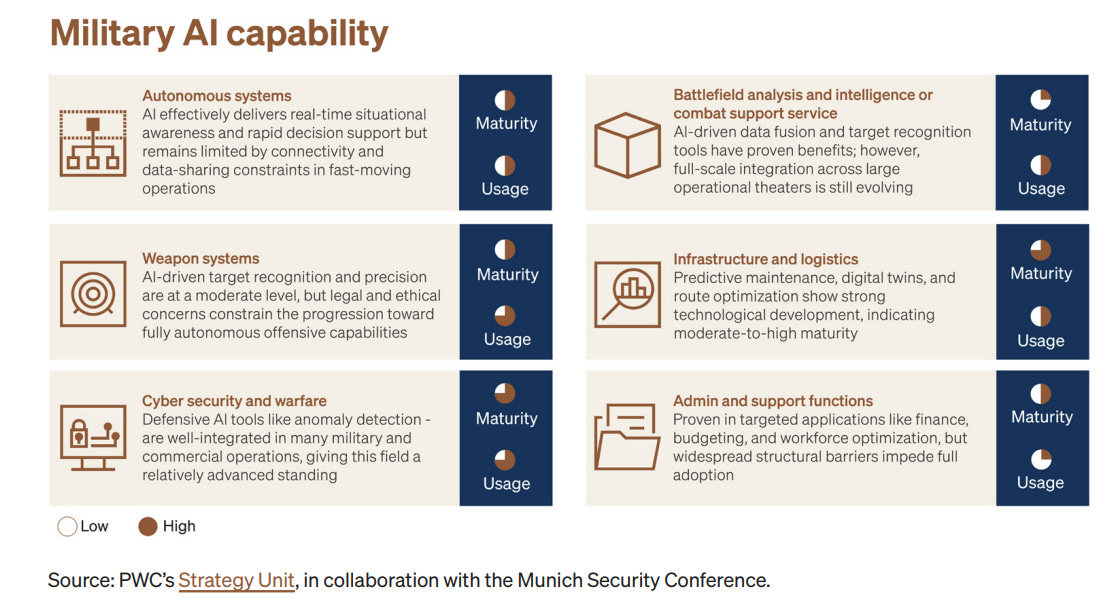

AI is redefining military power. In the final axis, JPMorgan writes that “artificial intelligence is rapidly becoming the decisive factor in modern warfare and national security strategy,” reshaping everything from procurement to battlefield operations (p. 29). The report notes that machine learning, autonomy, and computer vision are compressing the traditional “see–assess–decide–act” loop, creating a new kind of decision advantage in combat. In Ukraine, AI-powered intelligence (combining satellite imagery, open-source data, and automated analysis) has shown how near-real-time insights can transform warfare (p. 29).

AI also enables swarming tactics. Low-cost, autonomous drones and unmanned vessels are disrupting the logic of expensive, slow-built defense systems. The shift toward mass, adaptability, and distributed lethality is challenging older industrial models that relied on boutique production runs (p. 29). Meanwhile, U.S. firms like Anduril, Shield AI, and Palantir are outpacing traditional defense contractors in speed and innovation, though scaling those advances across allied militaries remains uneven (p. 29).

JPMorgan highlights growing competition from adversaries. China is embedding AI into its doctrines for cyber, space, and electronic warfare, aiming to offset U.S. advantages through asymmetric tactics. Russia, too, is testing AI-based targeting and countermeasures in Ukraine (p. 29). These trends underscore the need for counter-AI capabilities such as red-teaming, deception, and algorithmic resilience.

The report concludes that AI is now “not a sidecar technology for defense—it is the driver.” Nations that can integrate AI into force design, scale production, and align industrial capacity will hold a decisive edge (p. 30). For the U.S., that means closing the gap between innovation and acquisition and strengthening public–private collaboration to sustain deterrence in the age of intelligent warfare.

Conclusion – What We’re Watching

JPMorgan closes with a forward-looking scan of geopolitical and market signals that could shape AI’s next phase (p. 31).

The European Union’s digital omnibus package, expected in late 2025, will reveal whether Brussels’ promises of “regulatory simplification” translate into genuine flexibility for the AI Act. India’s 2026 Global AI Impact Summit will test how emerging markets use convening power to balance between U.S. and Chinese influence. Progress on the U.S. AI Action Plan will depend on how quickly agencies align on infrastructure, deregulation, and security execution.

Shifts in export controls will continue to determine China’s access to advanced chips and AI models, while diverging AI standards at the OECD and ITU could expose new openings for Beijing’s diplomacy. Meanwhile, the Middle East’s infrastructure investments are quietly redrawing technology alliances through energy-backed data centers and chip deals.

Defense timelines remain another barometer: the U.S. Department of Defense’s milestones for scaling autonomous systems will indicate how fast militaries can adapt. Beyond security, JPMorgan flags the risk of an “AI bubble,” noting that capital pouring into data centers and chips could exceed near-term earnings if revenue growth fails to keep pace.

Finally, the report warns that the Global South remains underrepresented in shaping the AI landscape. While its data, users, and talent are vital to global adoption, few strategies ensure equitable participation. This theme on how to make AI’s gains more inclusive will be a crucial topic at the 2026 AI Impact Summit in India (p. 31).

References

JPMorgan Chase & Co. (2025). Decoding the New Global Operating System. Center for Geopolitics, JPMorgan Chase & Co. Available: https://www.jpmorganchase.com/content/dam/jpmorganchase/documents/center-for-geopolitics/decoding-the-new-global-operating-system.pdf